Propaganda & Rhetoric

Propaganda is a tool that uses, “information, ideas, opinions, or images, often only giving one part of an argument, that are broadcast, published, or in some other way spread with the intention of influencing people’s opinions”[1], with disregard for objectivity and fact. However, in order for propaganda to work it needs to be convincing. Propagandists need to make their audience believe that they are a credible source and that the information they are communicating is true. This can be done through the use of rhetoric, Cambridge Dictionary defines as, “speech of writing intended to be effective and influence people.”[2]. Rhetoric makes use of the ambiguity of language and rhetoricians use tools like figures of speech to make their arguments more convincing. Rhetoric mainly uses two main forms of figures of speech; schemes, which rearrange word patterns for emphasis and new sentence meaning, and tropes, which extend the meaning by substitution, comparison, or transformation[3]. Rhetoric dates back to ancient Greek oral traditions and was used heavily by Greek philosophers.

For some, rhetoric is viewed in a negative light with both Plato and Socrates voicing their concerns about the use of rhetoric in argumentation. For example, in Gorgias, Socrates states that, “rhetoric trades more in appearances and wit than in truth or justice”[4], highlighting his worry that rhetoric can be used dishonestly. However, not everyone had such a negative view of rhetoric; Aristotle viewed rhetoric in a more pragmatic light thinking that it was useful and necessary for political discourse. Aristotle broke rhetoric up into three modes of persuasion: 1) Logos, which is reasoned discourse, logic, and dialectic or argument; 2) Pathos, which appeals to emotions, sympathies, or imagination; 3) Ethos, which appeals to the speaker’s moral character as perceived by the audience. A good argument makes use of each of the three forms of persuasion in order to shift an audience’s point of view in favour of the orator, “Ideally, the successful argument uses credible evidence, emotional conviction, and personal character to influence the judgement.”[5]. For “good” or true arguments, rhetoric is useful for guiding argumentation and Aristotle’s three forms of persuasion can serve as useful guidelines for the formulation of effective arguments.

The Dangers Associated with Rhetoric

On the face of it, rhetoric is a useful tool for argumentation, however we run into trouble when rhetoric is used in order to mislead an audience or convince them that something false is true. Rhetoric is an exceptionally effective tool when trying to shift an audience’s point of view because of how easy it is to disguise the use of rhetoric. A person’s use of rhetoric is often obfuscated from the public, with audiences often failing to recognize when tools of rhetoric are being used[6]. For instance, someone running for office may relate to their audience by stating that they are a businessman instead of a politician. According to Aristotle, this would be an appeal to Ethos, or the politician’s moral character as a businessman, with a set of values, qualifications, and beliefs different than those of the usual politician. This form of identification draws people’s attention away from a person’s actual qualifications and instead appeals to the public’s biases, which propagandists hope will make them appear more favourable in their audience’s eyes.

Another common rhetorical tool is making appeals to emotion, often glazing over details, by making rousing speeches or statements, “beginning with actions and events in a plausible world, … [building] a ladder of identification from sense impressions, to symbols, to transcendent narratives motivated by belief or faith”[7]. Often, we’ll see speakers increase the dramatic aspect of their speeches or arguments by warning about a descent towards tragedy should action not be taken. This style of communication is incredibly common in politics, where politicians will make statements about how if a vote doesn’t go their way the opposition will impose something terrible on the country. For example, Justin Trudeau began the 2019 Canadian election with this speech,

Politics is about people, maybe you’re a recent grad or a new Canadian, maybe you’re raising your kids or living out your golden years in retirement. Whoever you are, you deserve a real plan for your future. We’ve done a lot together these past four years, but truth is, we’re just getting started. So Canadians have an important choice to make. Will we go back to the failed policies of the past, or will we continue to move forward? That’s the choice. It’s that clear. And it’s that important. I’m moving forward for everyone.[8]

In his speech Trudeau adeptly makes use of Pathos and Ethos. He begins with Pathos, appealing to the public by saying that they need a real plan for the future. He further links himself to his audience by using the word, “we”, and saying that together progress has been made. Next, he asks Canadians to imagine a choice where one option is failed policy, an example of descent towards tragedy, and the other option is forward motion, in this case voting for the Trudeau government. This is also an example of a false dichotomy, although it may sound good it inaccurately represents the available options. Trudeau closes off the speech with an appeal to Ethos. He aligns himself to the obvious positive choice, forward movement and says that no matter what he will be making sure that everyone moves forward, making an appeal to his own moral character. I don’t wish to touch on the truth of Trudeau’s speech as that will likely depend on your political alignment. However, Trudeau’s speech is without a doubt emotionally charged and the idea of movement forward does glaze over some of the controversies that the liberal government had been involved in over the course of the previous years, namely first nations issues, pipelines, and most recently the SNC-Lavalin scandal. So, in this case we can see that rhetoric is used to draw attention away from some details in order to frame the Trudeau government in a favourable light prior to the election.

Twitter’s Role In Propaganda

Twitter serves as an excellent platform for the propagation of propaganda. With 330 million users, Twitter has an incredibly wide reach, making it very useful for the quick dissemination of information. Tweets are short making them quick to consume and readily available to anyone with access to the internet. In recent years, Twitter has famously been used as a disinformation tool during the 2016 US Election[9] and during the UK’s vote on Brexit[10]. Additionally, Twitter faces a problem with bots, with estimates ranging between 9% and 15% of English-speaking Twitter accounts being bots[11]. Bots disseminate information through twitter artificially increasing the popularity of certain hashtags or promoting articles and pieces of information to users. Bots therefore can have a profound impact in the spread of disinformation and propaganda across the social media platform. In a study by Kellner, Rangosch, Wressnegger, & Rieck (2019), it was found that during the German federal election, “the political landscape heavily relies on propaganda on social media”[12], which raises concern over social media platforms, like Twitter, being manipulated to promote certain politicians and parties.

One politician famous for his use of Twitter is US President Donald Trump, who tweeted 8945 times over the course of two years after his declaration of candidacy for the Republican party on June 16, 2015[13]. President Trump is able to communicate information publicly through Twitter in an incredibly efficient manner. Through Twitter, Trump avoids using official political channels and instead is able to get his message across in a much more casual and accessible manner. But Trump’s reach is not limited to just Twitter users, information shared on Twitter is then shared person to person, just like information learned in newspapers, “Those who did not read newspapers were influenced by those who did and ‘forced to follow the groove of their borrowed thoughts. One pen suffices to set off a million tongues’”[14], or in this case, one tweet.

A Case Study

Donald Trump serves as an excellent case study for examining the use of rhetoric on Twitter because he tweets so much, 28.1 tweets per day between July 20, 2019 and January 19, 2020, to be exact[15]. Furthermore, because Trump is a divisive political figure, the majority of his tweets are about very polarizing topics which helps to clearly illustrate his ideology and background for argumentation. I will analyze the language of Trump’s tweets using Aristotle’s model of rhetoric.

1.0 Covid-19 Test Rates

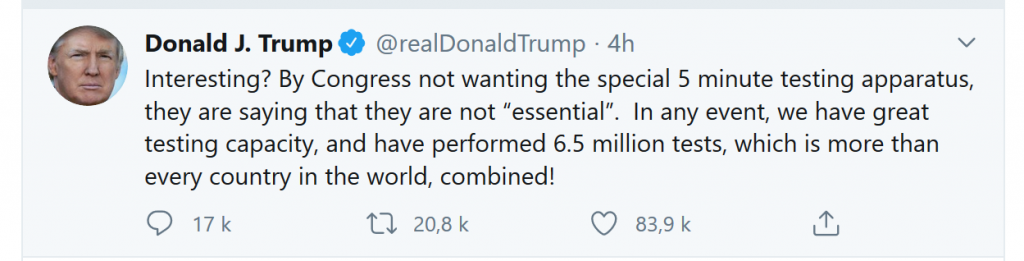

On May 4th, 2020, Donald Trump tweeted the following:

First lambasting congress and second boasting about the testing capacity for Covid-19 in the United States. Let’s focus in on the discussion about testing capacity. Lack of testing has been used to attack the Trump administration’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic. So, the topic of testing capacity became an important issue for the Trump administration in the effort to promote the idea that the Trump administration has handled the spread of Covid-19 effectively.

1.1 Logos

In this tweet Trump focuses on testing numbers in order to argue that his administration has effectively responded to the Covid-19 pandemic, because the US has conducted more tests than every country in the world combined. A problem that becomes apparent here is that countries greatly vary in their population numbers, thus touting a total number of tests may be misleading in regard to testing performance. According to covidtracking.com, the US had conducted 6,579,081 tests on May 1st, 2020[16], which aligns with the number of tests tweeted by Trump, therefore we will use May 1st, 2020, as our data point. The two other countries we will compare US testing to are Italy and Turkey, which have the next highest number of tests according to Our World in Data. At this point, Italy had conducted 2.05 million tests and Turkey had conducted 1.08 million tests, compared to the US’s 6.57 million[17]. So, lets compare these numbers to the total population of each country in order to see what percentage of each country’s population is being tested.

| Country | Population | Number of Tests | Population Tested (%) |

| US | 3282000.00 | 6579081.00 | 2.00% |

| Italy | 603600.00 | 2050000.00 | 3.40% |

| Turkey | 820000.00 | 1080000.00 | 1.32% |

From this table we can see that although the US has high testing numbers it is not testing the highest percentage of its population. Testing efficiency in the US, as of May 1, 2020, was actually worse than the testing efficiency of Italy, who tested 1.7x the percentage of their population compared to the US. Trump is correct that the US had conducted the highest number of tests overall, however the information conveyed in this tweet is misleading. Total testing numbers do say something about testing capacity, however when your population is as large as the US’s we should expect that the total number of tests will be incredibly high, especially when compared to a country with 18% of your population, like Italy. What is more important in this context is the number of tests per capita that a country is able to conduct, as this accurately represents how efficient the country has been in making testing accessible to its population. When the government response is inadequate it will be more difficult for citizens to get tested, which causes tests per capita to be lower than other countries with better testing capacity. Smaller countries are obviously going to have a lower number of tests conducted because they have smaller populations, but that isn’t indicative of a failure in testing capacity or efficiency. Trump capitalizes on the US’s large population, tweeting about total tests conducted, glossing over tests per capita, because it makes him and his administration look better. However, in reality at the time of his tweet, the US trailed in the actual testing efficiency to a country with 18% of their population.

1.2 Pathos

Trump’s tweets often make use of emotional language and rhetoric, utilizing the concept of Pathos. In this tweet, Trump appeals to the emotions and imaginations of the public in presenting America as having a fantastic handle on the Covid-19 pandemic because they have “great” testing capacity. Trump glosses over the fact that at that moment, the US had worse testing capacity per capita than Italy, and was only testing .68% more of their population than Turkey. By utilizing this appeal to emotion Trump doesn’t need to present the facts in order to create a convincing tweet. Instead, he only needs to appeal to his audience’s idea that he is handling the pandemic well and that America as a whole is a great country. Emotion clouds factual judgement and in this case, allows Trump to present a much more positive situation than the situation that really exists.

1.3 Ethos

Trump makes use of the words, “they”, and “we”, in this tweet in order to identify himself as a member of the successful group. He identifies congress as the other, by using, “we”, stating that because they don’t want his five-minute tests, they must not be essential. Then, he aligns himself with the apparent success of the US’s testing capability by saying that, “we have great testing capacity, and have performed 6.5 million tests”, implying that he, as a member of the collective we, has helped to improve testing capacity and thus help tests to be performed. This paints him in a more positive light, therefore increasing the chance that he will be perceived in a positive manner by his audience.

2.0 Lamestream Media & the Invisible Enemy

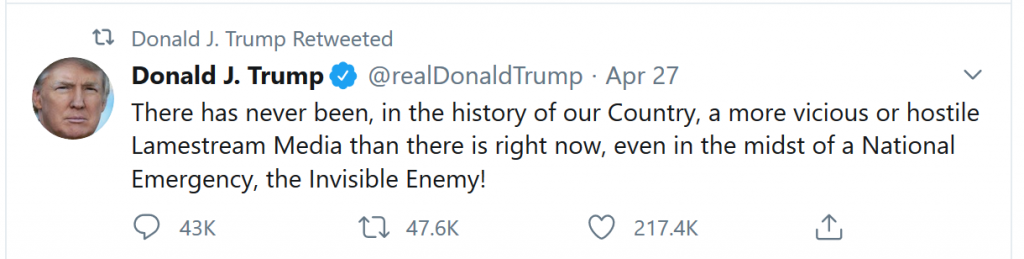

On April 27, 2020, Trump tweeted:

This tweet focuses on how the media has been critical of the Trump administration’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic in the US. Trump states here that the media is being unfair and treats him worse than any other president. He further identifies that the media is doing this during the pandemic which he identifies as the, “Invisible Enemy”, rather than Covid-19 of the Coronavirus.

2.1 Logos

This tweet doesn’t appear to utilize logos in any credible capacity. The idea that the media has never been more vicious, or hostile would be difficult to factually verify since people’s perception of the media will most likely be changed by their own political affiliations and personal philosophies.

2.2 Pathos & Ethos

Twitter communities are built in a way similar to how talk radio hosts build their communities, around, “shared language, beliefs and values”[18], which allows community members to feel included and understood. In this tweet, Trump uses two main pieces of language that help build inclusivity within his audience, “Lamestream Media”, and “the Invisible Enemy”. This use of language does two things, first it identifies Trump as a member of the community that he has built. He appeals to his audience by showing that he is a member of the community, which effectively increases his credibility with his followers. Obviously, his followers already believe in his moral credibility, however Trump’s use of language serves as a reminder that they have a shared sense of community and values that are important to the group as a whole. Secondly, Trump’s use of language makes an appeal to emotion, which according to rhetoric, serves to make his statement more convincing. When we hear, “Lamestream Media”, we might imagine media companies who are bad at their jobs and fail to accurately report the news. We no longer imagine well established media groups, with long professional histories, instead we are to imagine that they are useless. This makes it easier for Trump to pit people against the media and paint them as the enemy of the people. Using the term, “the Invisible Enemy”, also separates the concept of Covid-19 from the actual pandemic. Covid-19 is no longer a disease ravaging the country, it is now an enemy hiding in the shadows that must be conquered. By doing this, Trump is able to evoke a feeling of a collective group against the evil outsider. This use of language enables Trump’s audience to view themselves as fighting against, “the Invisible Enemy”, rather than being at the mercy of a deadly disease. The tweet transforms Trump from a leader being criticized for inadequately dealing with a pandemic to a man victimized for trying his best to fight against an invisible foe.

3.0 Presidential Election

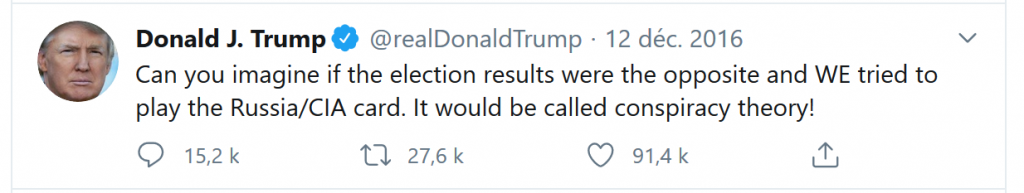

On Dec. 12, 2016, Trump tweeted the following:

This tweet focuses on Trump’s outrage about the results of the US presidential election being investigated on suspicions of Russian interference. Trump wishes to protect the validity of his win and so he attacks the idea that Russia had any role in the outcome of the US election.

3.1 Logos

This tweet does not appear to make use of Logos. It doesn’t feature any reasoned discourse or use of logic in order to convey its message.

3.2 Pathos

In this tweet, Trump asks his audience to imagine what the response would have been if he had lost the election and then called for an investigation into Russian interference. He appeals to the imagination and emotions of his audience, to imagine how they would be treated if that were the case. His appeal to emotion is meant to convince his audience that if it were the other way around, they would not be taken seriously and therefore, calls for investigation into the election from the Democrats should not be taken seriously. This tweet tries to convince his audience that the investigations are unnecessary, rather than a logical step to be taken when concerns about the integrity of an election are called into question. Trump’s tweet effectively plays into the emotional feelings of his supporters in order to convince them that an investigation should not occur.

3.3 Ethos

Trump’s use of Ethos in this tweet is fairly evident as he has capitalized, “WE”, in order to identify himself with his supporters. By doing this, he makes calls for investigation not just an attack on the credibility his presidency, but an attack on his supporters as well. Trump involves his community of supporters in the struggle thus making an appeal to his own moral character alongside the moral character of his supporters. This helps him to paint the calls for investigation in a negative light as it calls into question the integrity of his entire community rather than just Trump’s integrity.

4.0 Some Further Examples

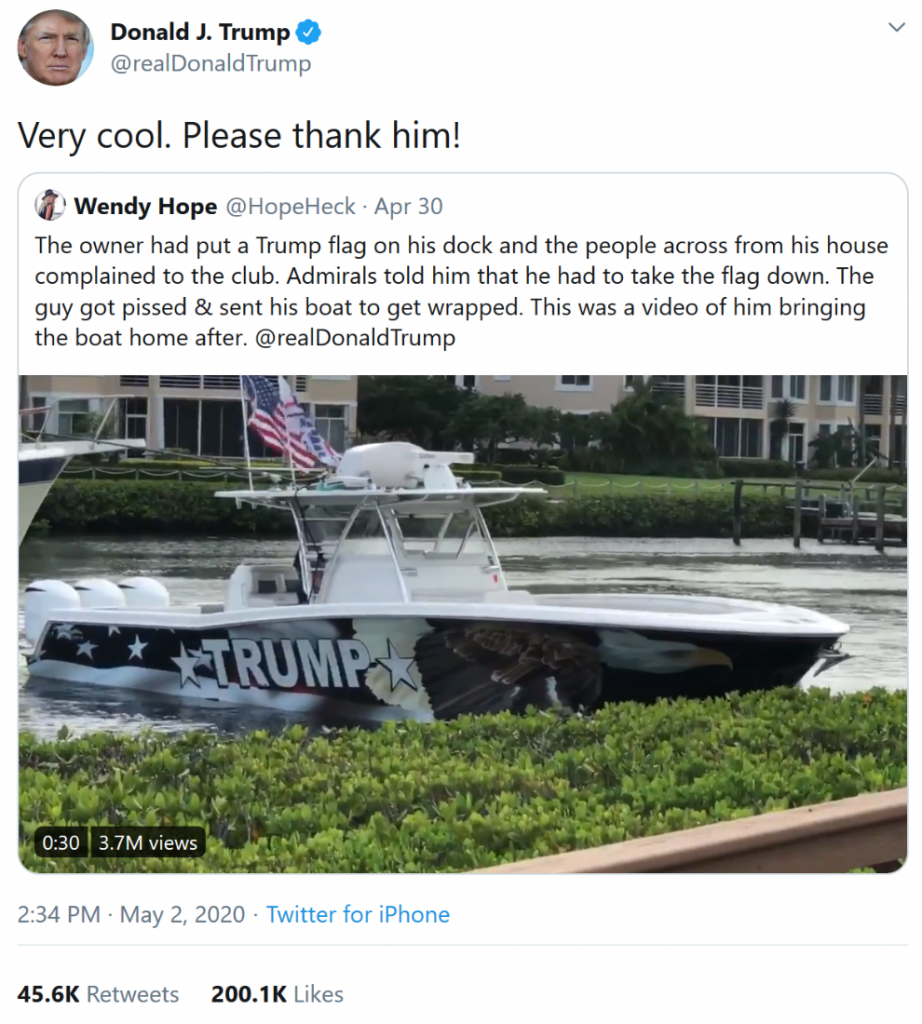

Trump is also incredibly adept at appealing to his base in a casual, non-presidential, way. For example, Trump often retweets posts from his supporters, making them feel included in conversation, and will often tweet support in a casual way that is not often associated with politicians.

This tweet is an excellent example of Trump’s communication with his base. He uses very basic everyday language and reposts something from a community member. This helps to promote a feeling of inclusion and dialogue with his followers which in turn improves his base’s opinion of his moral character. On top of this, tweets like this help to identify Trump as a political outsider, different from other politicians and therefore potentially more likeable and appealing to the average person.

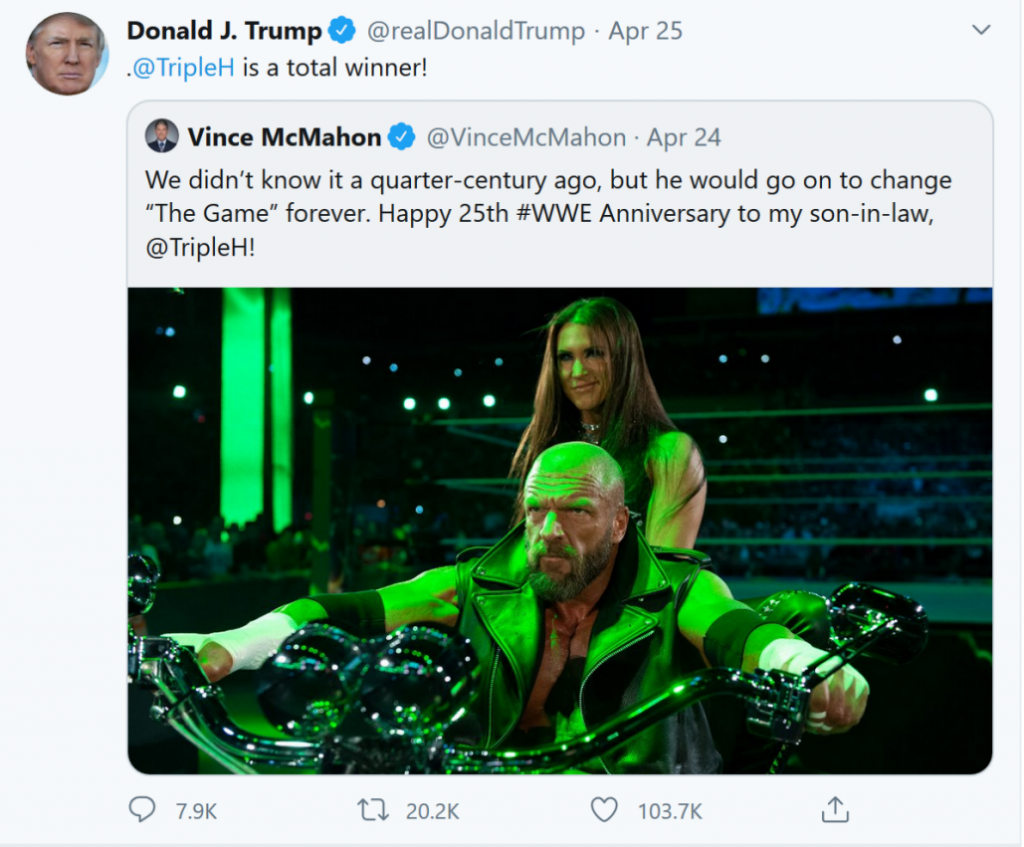

In a similar vein, this tweet about Triple H is casual and relatable to a wide audience. It is not overtly political, uses casual language, and references popular culture. Tweets like these help position Trump as different from other politicians and help foster a feeling of closeness and inclusiveness with his followers.

Conclusion

In conclusion, whether he realizes it or not, Trump heavily utilizes tools of rhetoric in order to promote his own narrative on Twitter. Although Trump’s tweets may not be the most refined pieces of text in the world, they do illustrate how rhetoric can be used to create convincing arguments. The fact that Trump and many other actors can utilize social media sites like Twitter to promote their own agendas and narratives is concerning because it can lead to large amounts of disinformation. Factual inaccuracies in tweets or social media posts are not always readily evident and can lead the public to believe misleading or false information. A recent example of this being Twitter’s controversial fact checking of one of Trump’s tweets about mail-in ballots[19]. In this case, Twitter recognized the misleading aspects of the tweet and intervened in order to provide better data, but this is not done for all potentially misleading tweets. It is therefore important that members of the public be aware of the use of rhetoric in online discussion so that they can recognize when a piece of information may be misleading. In closing, my hope is that rhetorical models like Aristotle’s will be helpful in furthering people’s ability to recognize misleading information online. Disinformation will be an ever-pervasive issue online, but hopefully a tool like Aristotle’s rhetorical model will prove to be useful in recognizing and combating this wide spread issue.

[1] “Propaganda”, Cambridge Dictionary, accessed June 6, 2020, https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/propaganda.

[2] “Rhetoric”, Cambridge Dictionary, accessed June 6, 2020, https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/rhetoric.

[3] Marshall Soules, Media, Persuasion and Propaganda (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015), p.29.

[4] Marshall Soules, Media, Persuasion and Propaganda (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015), p.22.

[5] Marshall Soules, Media, Persuasion and Propaganda (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015), p.22.

[6] Marshall Soules, Media, Persuasion and Propaganda (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015), p.24.

[7] Marshall Soules, Media, Persuasion and Propaganda (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015), p.26.

[8] Justin Trudeau, “Launch of 43rd General Election Campaign” (speech), ca. 2019 in “Liberals push vision as work-in-progress as they ask Canadians for 4 more years” CBC News, 0:49, https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/liberal-campaign-2019-election-1.5278453

[9] United States Department of Justice, United States of America v. Internet Research Agency (18 U.S.C.2,371,1349,1028A), 2018

[10] Samantha Bradshaw and Philip N. Howard, “The Global Organization of Social Media Disinformation Campaigns” Journal of International Affairs, 71, no. 1.5 (2018): 25.

[11] Onur Varol, Emilio Ferrara, Clayton A. Davis, Filippo Menczer, and Alessandro Flammini, “Online Human-Bot Interactions: Detection, Estimation, and Characterization”

[12] Ansgar Kellner, Lisa Rangosch, Christian Wressnegger, and Konrad Rieck, “Political Elections Under (Social) Fire? Analysis and Detection of Propaganda on Twitter” Computer Science Report No. sec-2019-01 (2019): 15

[13] “Archive”, Trump Twitter Archive, accessed June 6, 2020, http://www.trumptwitterarchive.com/archive

[14] Marshall Soules, Media, Persuasion and Propaganda (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015), p.59.

[15] “Archive”, Trump Twitter Archive, accessed June 6, 2020, http://www.trumptwitterarchive.com/archive

[16] “US Historical Data”, Covid Tracking, accessed June 6th, 2020, https://covidtracking.com/data/us-daily

[17] “Total COVID-19 tests”, Our World in Data, accessed June 6th, 2020, https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/full-list-total-tests-for-covid-19

[18] Marshall Soules, Media, Persuasion and Propaganda (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015), p.24.

[19] Thomson Reuters. “Twitter places fact-check notification on Trump tweets about ‘fraudulent’ mail-in ballots.” CBC News, https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/twitter-fact-check-trump-tweet-mail-in-ballots-1.5585798